The moments that define the course of our lives

The day I almost died started like an ordinary day. I had just finished clinic. I felt a little out of breath, but nothing alarming. Just a week before, I was given a clean bill of health. Within minutes, I was out. Both of my lungs packed with clots. A massive saddle pulmonary embolism. The kind people don’t usually survive.

As I lay in the ICU, oxygen mask pressed to my face, I kept thinking: How does someone who did everything “right” end up here? And how did we all miss this?

I didn’t know the answer then. But I do now. That event propelled me to seek answers, which resulted in building a company dedicated to ensuring no one else gets blindsided by their hidden risks.

Once you learn what I am going to share with you today, you will understand why normal cholesterol or LDL means nothing, absolutely nothing, about your true cardiovascular risk or risk of dying.

Your standard labs are not enough

I did not plan to start with my story or even this topic for my inaugural edition. But in the past few months, three people close to me developed blood clots. Two of them were women under fifty and in perimenopause, like I was. One had a stroke (a blood clot in the brain), One had a leg clot.

They had their annual physical. Like me they had a false sense of security and belief that annual labs tell you the truth about your health.

So, both of them were blindsided when we uncovered their genetic wildcard not assessed on their standard labs: elevated lipoprotein(a), or Lp(a), pronounced lipoprotein little a.

Not surprising, considering that 1 in 5 people carries elevated Lp(a) that can triple their risk of heart attack or stroke.

Lp(a) can quietly accelerate vascular aging for decades, shaping your heart, brain, hormones, muscles, metabolism, and ultimately, shortening your healthspan (years you live in good health).

If you have never heard of Lp(a), you are not alone.

If your doctor hasn’t ordered it, they are not alone either.

And if your last cholesterol panel came back “normal”? Well, “normal” depends heavily on what wasn’t measured.

Quick hello before we begin

I am Dr. Adrijana Kekic, a pharmacist for twenty years, a chocolate lover for twice as long, and founder of Futurome, where we go beyond standard testing to understand health at the cellular level.

If you came from my LinkedIn newsletter (The Future of Health Is Now), good to see you again! Longevity deserves more than trendy biohacks and supplement-of-the-week hype. Even the term “longevity” confuses. If you are new, drop me a comment - I read them all. And welcome here!

My philosophy is simple: Know your cells to know yourself.

This newsletter is where my clinical insights and curiosity meet scientific rigor. There is something for everyone, so navigate your experience:

Part I — Flyover (under a minute summary of what you need to know on the topic)

Part II — Ground Work (practical insights for patients and providers under 5 min)

Part III — Deep Dive (paid masterclass for my fellow science nerd - you will need a notebook and some coffee).

I. FLYOVER

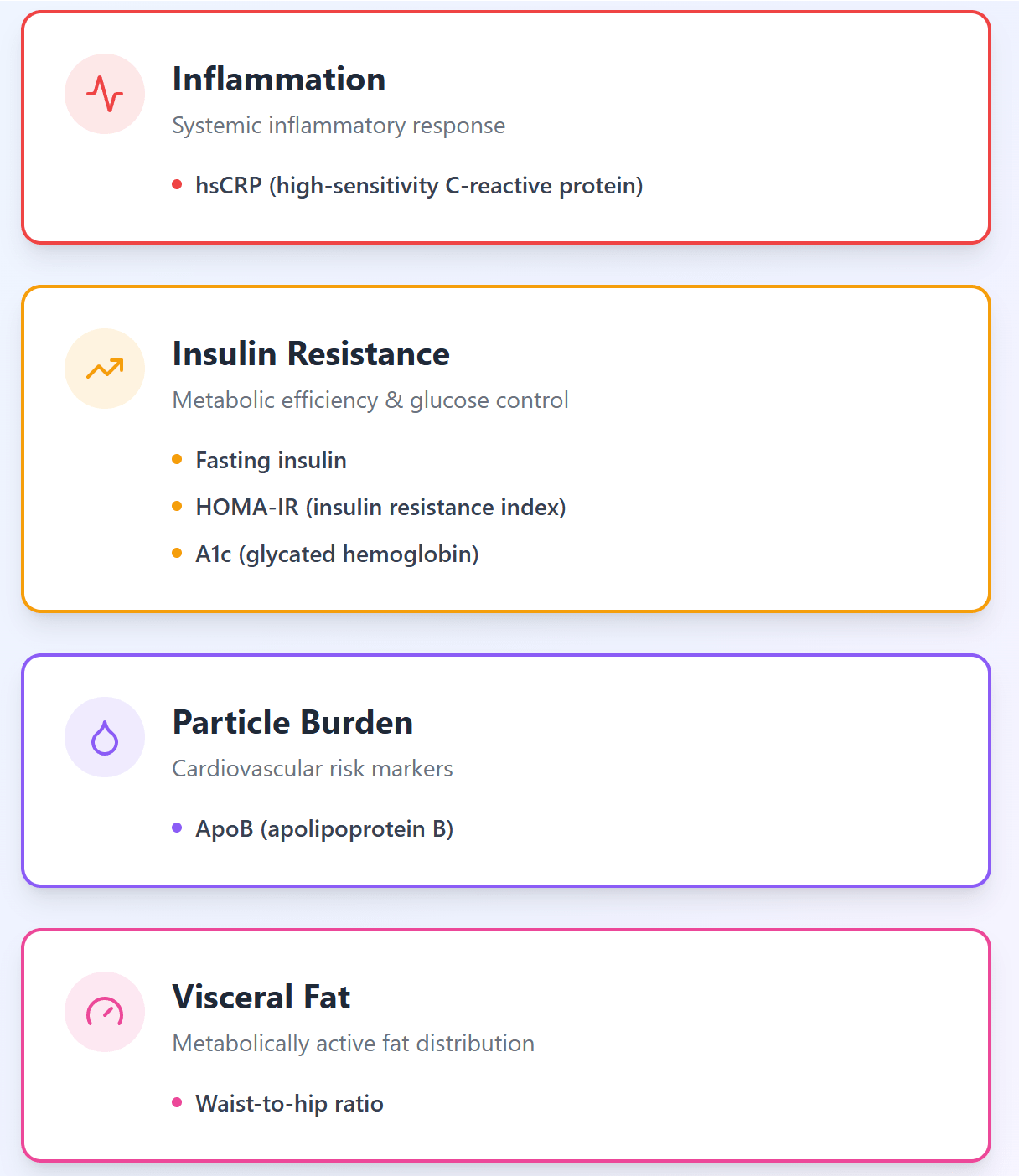

Lp(a) is an amplifier of cardiovascular risks. To reduce is you need to manage inflammation, insulin resistance, ApoB, visceral fat, endothelial health, hormones, and support mitochondrial function. In this newsletter I will tackle the following:

II. GROUND WORK

1. Lp(a) is LDL’s dangerous cousin (but context matters)

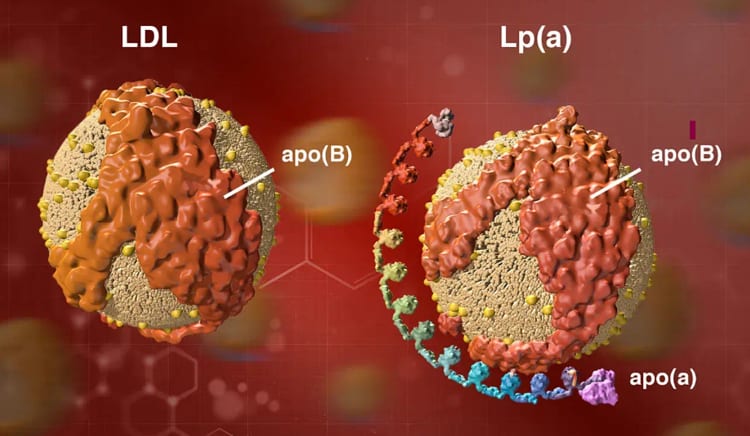

Lp(a) and LDL (low-density lipoprotein) are both lipoproteins. They look alike. That is why the standard testing may “confuse” them. You heard LDL called “bad cholesterol.” There is no such thing as good or bad cholesterol. Let’s do a bit of myth busting shall we?

Myth 1. Cholesterol causes heart disease. False- Cholesterol is an essential molecule of life. You can’t live without it.

Myth 2. LDL and Lp(a) are bad cholesterol. False - Neither is actually a cholesterol. They are its carriers. Like delivery trucks, they load up and transport essentials to your cells: cholesterol, antioxidants, nutrients, fat-soluble vitamins, etc. Your brain, hormones, muscles, and cell membranes – they all love cholesterol.

Now it is true that Lp(a) is a bit tricky. It’s still a delivery van, but with a sticky grappling hook that acts as a torch blower. That sounds bad, right!? Yes, it can be (notice I said “can” and not “is”).

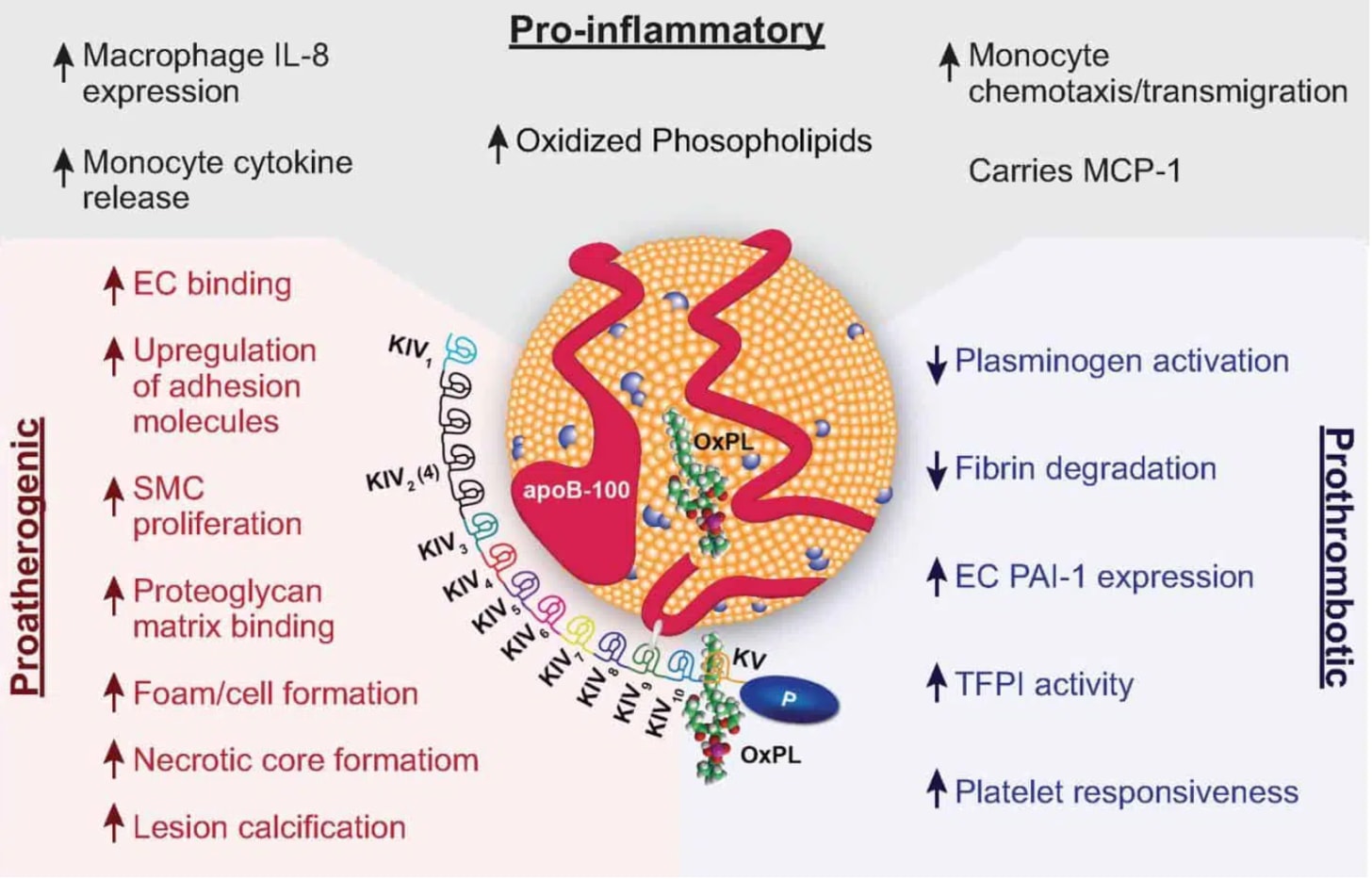

What can make it dangerous? Lp(a) is an LDL-like particle with an extra protein tail called apolipoprotein(a) attached to APO-B (more on this in part 3). That tail can increase risk of blood clots, under the right circumstances, because it can:

stick more easily to artery walls,

carry oxidized lipids that inflame vessel lining,

interfere with your body’s ability to dissolve clots,

and accelerate calcification of arteries and heart valves.

This is why you can have normal LDL numbers … and Lp(a) can still be quietly eroding vascular health in the background. And yet, not all people with high Lp(a) will have cardiovascular events. Wait, that doesn’t make sense! So who is at risk??

2. One in five people have high Lp(a). Most have no idea

Roughly 20% of us have elevated Lp(a). If you put five friends around a dinner table, chances are one of them has it, and probably doesn’t know it.

This is what keeps me up at night - folks who “look fine” but are not. I was eerily reminded of that just a few months ago.

The 49-year-old with a brain clot. A healthcare professional, relatively healthy, with a personal and family history of hypertension and autoimmune diseases. Not necessarily a picture of a transient ischemic attack waiting to happen.

The 47-year-old with the leg clot. A fellow founder with normal labs from a yearly physical. Ran daily and wore an Oura ring.

Neither was obese nor injured. Neither had the usual genetic red flags: no Factor II or V mutations. Neither were on HRT or birth control before their events. All of these are known risks for clots.

But here is what they did have in common: both were women in perimenopause, juggling demanding lives & chronic stress. And no one had ever tested their Lp(a).

When we finally ran advanced labs, the real story emerged. High Lp(a), early metabolic shift to reduced insulin sensing marked with high insulin and above normal A1c (average blood sugar over 3 months), elevated inflammation marker, and biological ages almost a decade ahead of their calendars.

I call this a blind spot of a perfect biological storm, not bad luck.

3. You can’t out-exercise or out-eat your Lp(a) genes

Here is the part people don’t love, especially my marathoners and biohackers – I have seen ultramarathoners with sky-high Lp(a) and people with questionable diets with very low Lp(a).

Over 90% of your Lp(a) level is genetic. It is driven by the LPA gene and the number of “kringle IV” repeats in that sticky protein tail. Think of kringle repeats as speed bumps. More speed bumps slow down Lp(a) production, translating into a lower risk of heart attack, stroke, and blood clots (in the right context).

So, if you have variants of this gene that increase your Lp(a) are you doomed? Are genes your destiny? No, they are not. It just means you can’t negotiate with it through lifestyle or medications (at least not yet). So, what’s the good news, you ask? Knowing your levels can help you more precisely manage the CONTEXT in which genetic risk EXPRESSES itself:

High Lp(a) + high ApoB = much higher risk

High Lp(a) + inflammation = much higher risk

High Lp(a) + insulin resistance = much higher risk

Lp(a) is an AMPLIFIER, not a lone culprit.

Remember how I compared it to a truck with a blowtorch. The good news is that the little a is not usually the fire starter. Think of it as the gasoline that makes other risks burn hotter. That means that you can modify your other risks (see part 5 bigger picture) and reduce those associated with the little a.

Why this matters:

If your Lp(a) is high, your margin of error is smaller, but your destiny is not set in stone. You can work on things you have control over like blood sugar control.

4. Standard cholesterol panels do not assess Lp(a)

This explains why two people with the same LDL and blood pressure can have dramatically different cardiovascular outcomes. You can have a “great” lipid panel and still have a problem.

Most standard tests look at:

total cholesterol,

LDL-C,

HDL-C,

triglycerides.

Lp(a) is usually not included. Worse, the cholesterol inside Lp(a) particles gets counted as part of your LDL-C. Your LDL-C may look “normal” while a chunk of it is actually Lp(a)… which behaves, as you now know, very differently. That means “normal cholesterol” is not the whole story.

5. You only need to test Lp(a) once in your life

The big organizations (American Heart Association, European guidelines, etc.) now recommend at least one Lp(a) measurement in adulthood.

Because it is so strongly genetic, Lp(a) is fairly stable across your lifetime. One well-done test is usually enough to know your baseline risk (based on our current knowledge).

A simple way to think of the ranges (your lab report may show mg/dL or nmol/L):

Optimal: less than about 30 mg/dL (or 75 nmol/L)

Elevated: above about 50 mg/dL (125 nmol/L)

High risk: above about 100 mg/dL (250 nmol/L)

If yours is low? Great. One less variable to worry about. You still have to live like a human with arteries, but at least this particular fire is not burning.

If yours is high, that is your cue to zoom out and look at the BIGGER PICTURE:

Want the Full Deep Dive?

If you’re a clinician, health professional, or just a very curious human, you’ll find the nerdy details there.

[Upgrade to paid subscription]